GOALS AND RESOLUTIONS FOR 1998

Rich Mullins, musician and writer, 1955-1997

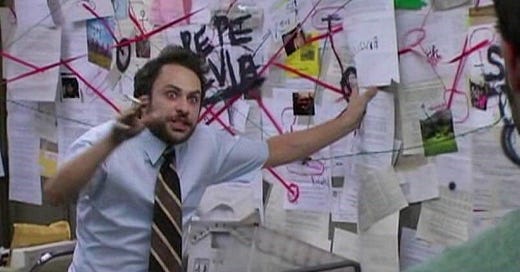

Why have we lost faith in institutions? The picture above explains why, and throughout this series, I will be exploring where that faith has collapsed in the various points in the complex web that is modern life. Before we can understand why faith has failed in institutions, we need to understand what institutions do in modern times. But to understand what institutions do, we need to understand what we do as people that motivates the need for institutions. But to understand what we do as people, we need to understand how people often develop (or don’t) in modern times and how that motivates what they do. So, in the next entry of this series, I will dive into the left side of the diagram and, over successive posts, move to the right. And, perhaps, we will end up where we began. As people first.

In this post, I plan to explain how to read the diagram, provide a general overview of the ideas in the diagram, and then offer a brief reflection on the creation of the diagram.

How To Read The Diagram

Let’s start with how to read the diagram.

Start with the Person node in the top left. From there, you can trace several paths that people in modernity follow as they live their lives. I have included definitions on key nodes for clarity. On a personal level, you can focus on the Development node and see the stages many people go through as they grow up, encountering multiple perspectives in this big, diverse world we live in, which eventually lead to interaction with the Institutions node. On a more social level, you can focus on the Practices node to see how the things we do in our lives lead to and interact with institutions. On the level of civilization, you can focus on the Liberal Democracy node to note the ways that practices crucial to liberal democracy interact with institutions. You may even start to see some critical points where problems have occurred. I would welcome any of your thoughts on those critical points.

Overview of THE PROBLEM

What does it mean to live in modern times as a human being? According to MacIntyre (cited above), it means to accept that we simply cannot agree, as a species, on what a good life is. Just let that sink in. We do not all agree on what we’re doing here on this rock in space. Lots of people have lots of different perspectives on this crucial question on what the good life for people is. But how are we supposed to live good lives if no one agrees on what a good life is? This predicament is, perhaps, not unique to modern humans, but it is, nevertheless, a pretty fundamental experience of being a person navigating modern life.

To work through this predicament as individuals, facing all of these many perspectives, many of us have adopted a loose belief that the meaning you give to your life and what you do is dependent on context (a kind of weak relativism). What is true or valuable is influenced and shaped by the contexts in which we live. But we cannot simply stay in this position and adopt an “anything goes” attitude. We have to live. So we make commitments to personal values and choices. But where do we get these values and choices? We get them through engaging in practices.

Practices, again according to MacIntyre, are the social activities that we do to accomplish some good in this world by striving to achieve excellence in them. Practices, in other words, are something you can get good at. Football. Harmonica. Cooking. Journalism. Government. These are practices. But who or what determines what it means to get good at these practices? And who or what determines the good that we try to accomplish in a practice?

In short, institutions do. Institutions are organizations that regulate and facilitate practices by using material resources (e.g. money) and authority. But some institutions have started to define what is good in ways that a lot of us don’t agree with. We have been having a particularly hard time lately agreeing on what it means to be good at some practices and what good some practices are supposed to accomplish. And that is, basically, why I think we have lost faith in institutions. If we don’t agree with how they are defining “good,” why should we accept their authority?

This threat to institutions’ authority makes it difficult to maintain law and order in liberal democracies. Not only this, but the loss of authority indirectly inhibits our ability to achieve the societal goods that institutions provide. We are missing out. And it sucks.

That concludes my overview of THE PROBLEM WITH MODERN SOCIETY. At this point, analyses like these are a dime a dozen, and they’re often followed by a sales pitch to learn more and fix the problem—or they’re part and parcel of some bullshit your cranky uncle is going on about. I’m not special, and I could be wrong, and I’m not the smartest or most erudite writer to tackle this issue. But I’m not trying to sell anything, and I am not yet a cranky uncle. So, in lieu of the sales pitch, I want to offer a brief reflection that might persuade you to see things through this perspective.

The World As Best As I Remember It

This diagram is a culmination of my brief 37 years on this planet, piecing together parts of the puzzle of the world from life experience, three degrees including a doctorate, and a lifetime of reading. I am drawing heavily from the five books cited in the diagram, but there’s bits and pieces in there from long conversations with friends and family1 talking about these and other books; various arguments I’ve had in my head with Chesterton, Jesus, and Socrates; snippets of Stoicism (hint: desire); deep references to obscure tomes of Christian apologetics (namely Josh McDowell); and a healthy dose of what I have learned reading and teaching technical writing at MIT. In short, from what I’ve read and what I’ve seen, this is the best picture I could create of the world as best as I remember it.

And that brings me to Rich Mullins, who I have written about many times before, and whose words serve as the epigraph to this post. Rich produced two albums in the 1990s called The World As Best As I Remember It Vol. I & II. The title of the albums was taken from an exercise he would do before concerts sometimes. To lighten up in the face of the pressure of performing, he would draw on a white board a picture of the world as best as he remembered it. He would sketch an outline of the continents and then fill in as many countries as he could before showtime called. Before going to the stage, he would quickly scrawl: “This is the world as best as I can remember it, by Rich Mullins.”2

Rich’s Goals and Resolutions for 1998 from the epigraph bear witness to his desire to live his life in light of the vast and diverse world around him. Tragically, he died before he could see 1998. Rich saw the world as a big, beautiful, tragic, glorious set of scenery for the journey of life. I have often not seen the world this way. As you can see in the boxes and arrows, I have often seen it as a puzzle—something to understand, categorize, and analyze; a problem to be solved, eventually; a confusing morass of ideas and feelings; a forest so deep and dark that a few times I got so lost I couldn’t find my way out. But this year, in 2023, I did find my way out enough to peek my head up from the briars of 37 years. And I thought I’d hand you a map. This is the world as best as I remember it.

But a map is not the territory. It is a partial representation from a particular perspective. And I am not entirely convinced that this perspective is even the most important one. Because whether living in modern times or the neolithic, people like Rich have always stuck their heads out from the bushes to hand others maps—arguably, far more beautiful and meaningful maps of the world than what science and philosophy can render. Songs and poems. Paintings and sculptures. Liturgies and rituals.

I say all this to say that even though I worked hard on this, even though it is informed by the training I received in higher education learning how to work through difficult texts explaining complex knowledge drawn from science and philosophy, this map is only part of what I’m using to navigate modern life. But I hope you might find it resonates with you, seems accurate enough for the perspective it offers, and helps you understand what happened here.

The world is bigger than we can know.

Thanks to Aleks, Amanda, Josh, Jodie, Rachel, Daria, Nicole, Chuck & Charles, Emily & Jenna, Joy, Erec, Ryan, and Andres. Special thanks to Zeph. He worked through every draft of this thing over tea and long walks around Boston. You all made me do this. :)

Smith, J. B. (2002). Rich Mullins: A Devotional Biography: An Arrow Pointing to Heaven. B&H Publishing Group.