The Heterodox Academy 2024 Conference is ended, and it ended as it should: with conversation.

The final panel featured a discussion among several scholars on the question: “Where is the university going?” You can watch it here.

If you do not know who these people are, that’s good. Their stature should not weigh on the validity of their ideas. I was in a session earlier that day with Stanley Fish. I sat directly behind him, and I knew his name—he is a famous philosopher—but I did not know his face. And so, I had the pleasure to judge his views as I would any other person. During the questions period, he stood and opined (a comment more than a question) on much the same topic as what he discusses in this video. And, not recognizing him, I found him to be a cranky person with a decent point I wanted to think about more. And so, I invite you to sit back and think with me.

Throughout this discussion, I felt very much like I was living in a historical moment. The academy is a family of sorts. We have lineages. We have history. We have drama. And we have fights we’ve been having for literally millennia. This fight that I watched transpire on the stage felt very much like an ancient fight, one we’ve been having in the family for ages. And, God help me, we relish it. After the panel, my friends said they found the discussion “entertaining.” And I agree. And I also find the fight, in addition to being entertaining, to be important—perhaps, our most important fight.

This fight likely began in the first academy, which in the Western tradition, is Plato’s Academy in ancient Greece, where teachers and students conversed under the shade of the trees in the Academus Grove. And I have little doubt that at some point, under those trees, the seed of this fight took root when they asked each other, “What are we even doing in the academy?” In other words, what is our goal? In the Ancient Greek, this “goal” had a special word: telos. It means the ultimate aim or target of an endeavor—or even, the ultimate aim of life.

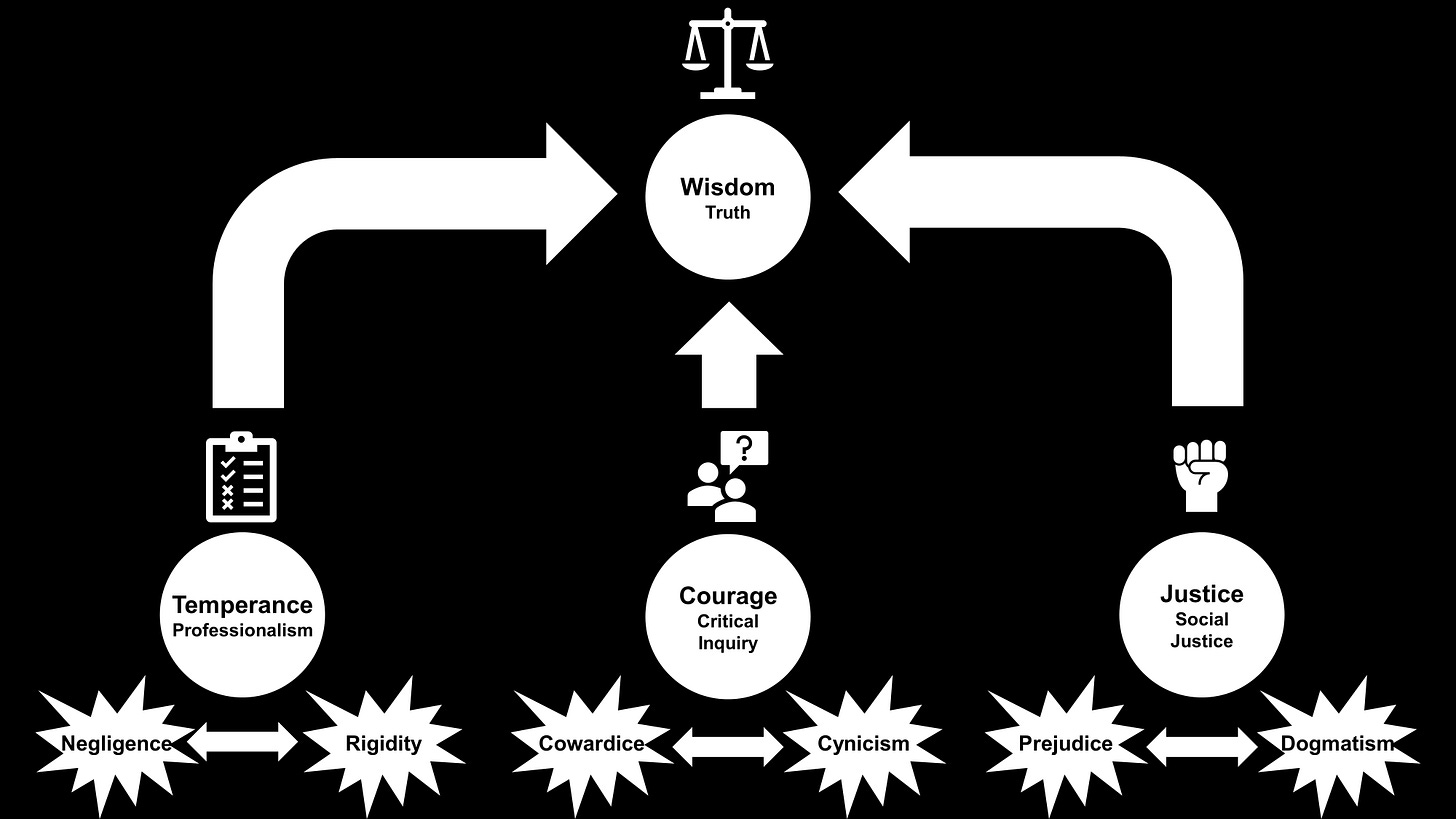

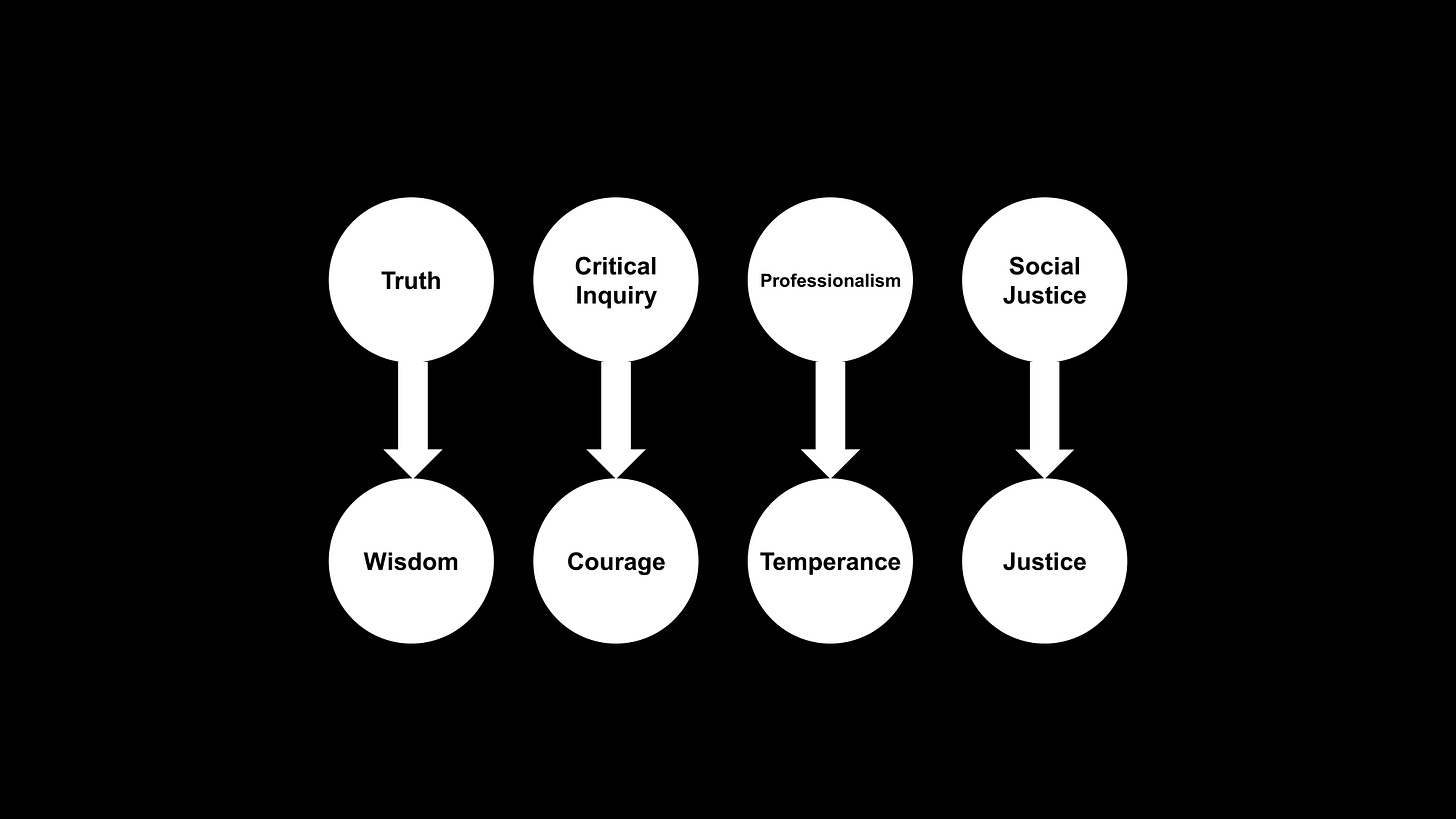

Many of the ancient Academics had an answer for this question: virtue. In the ancient Greek tradition, there are four virtues: wisdom, justice, temperance, and courage. Wisdom is the highest virtue, because it is the practical knowledge and skill to be able to know, in any situation, how to exercise the other virtues of justice, temperance, and courage. These virtues—and the status of wisdom as the overarching aim—gave me a framework to understand this conversation.

On the stage at Heterdox Academy, the scholars attempted to answer this same question: “What are we even doing in the academy?” What is the telos of the university? And they offered different answers—that’s why it’s a fight. But the answers, despite having different names now, are basically the same as they were thousands of year ago.

What are the answers? For perhaps the majority, the telos of the university is truth. Look at any crest of any university, and you are likely to see the Latin word veritas, which means truth. It is the commonsense aim of the university—it is what laypeople think is the point of a university education. You go to unversity to learn the truth about the world and people. And then you go out and apply what you learn. And because it’s true, it works well for you to accomplish your goals.

But there were challenges to this aim. Stanley raised the first objection. He argued that we are not in the university to seek truth primarily; we are there to be professionals and for our students to become professionals. Amna Khalid countered that instead, our aim is to engage in critical inquiry. In the background, unspoken but, in some way, the loudest voice, a third group of activist scholars countered that the telos of the university is social justice.

If you squint, you’ll see the shadows of the trees of the Academus Grove.

We can map these aims to the virtues that animated the ancient Academy. Social justice is an easy translation—just chop off “social.” Professionalism is harder—what are the attributes that characterize professionalism? According to the professional education organization MindTools, we can characterize professionalism as practicing certain dispositions: appropriateness, competence, reliability, integrity, and respect. In a word, these are attributes of temperance. Critical inquiry means to seek understanding through questioning—and, crucially, to be open to questioning everything, including and perhaps most importantly, our own beliefs. To do so requires courage, which, appropriately, was the final call to action by Nadine Strossen.

In the ancient practice, these virtues represented a mean state—a kind of middle ground between excess and deficiency. For example, someone who lacks courage is a coward. But someone who has, in a way of speaking, too much courage is rash. Someone who lacks temperance—well, we all know this one if we’ve ever eaten or drank too much. But to have too much temperance, we can look to Scrooge. Or we might eat too little—which we recognize as a warning sign of mental illness—or have no fun, which you can look to me as an example.

The same analysis can apply to these aims of the university.

To Stanley’s point, if we take professionalism as the aim, we run into problems of too much—leading to rigidity—and too little—leading to negligence. To Amna’s point, if we take critical inquiry as the aim, we can run afoul through cowardice or cynicism. And to the activist scholars, we have seen in the past decade both deficiency of social justice in the forms of prejudice—which they aim to fight—but also excesses of dogmatism, which many of them engage in. Interestingly, ChatGPT names “cancel culture” as one of the vices of excess social justice—which is one of the problems that motivated the founding of Heterodox Academy.

If we want to be able to avoid these deficiencies and excesses, we need wisdom. We need to see the world as accurately and truthfully as we can so that we can discern what exactly professionalism, critical inquiry, and social justice means in any given situation. These virtues are not self-evident, and they are not calcuable. They are found in living the life of the mind in communion with our colleagues; in challenging ourselves through exercises in thought and practice; and in cultivating dispositions through interacting with fellow experts, commonly-held canons, and the animating situations of our vocation: the classroom, the seminar, the library, the laboratory, and, appropriately, the conference.

Not to leave wisdom unquestioned, Amna rightly points out that truth is not self-evident and not arrived in the same way in all contexts. Truth is sought through the practice of disciplines, and the disciplines work towards consensus on what truth looks like—for example, in the quantitative disciplines, validity and reliability, but in the qualitiative disciplines, trustworthiness. They also work to find agreement on what counts as legitimate evidence and what methods best can guide us in our search for truth.

And the search—the direction, the living—that, is perhaps, the final word. No one on that stage seemed to maintain the idea that truth was ever a destination. That way lies dogmatism. It seems to me that all of the aims offered as the proper telos of the university were all of a piece—and that piece was the search for truth, the love of wisdom. Philosophy. Our degrees—Doctors of Philosophy—ought not to lose their lineage, back to the Academus Grove. The geologist I spoke to and undoubtedly annoyed with my questioning announced he himself was a philosopher—that we all were. And those without the degree—the opera singer at the group dinner at the burger joint who regailed me of the synthesis of the anatomy of breath and emotion, the research administrator on the plane home who commiserated with me on the challenges of academic life—are philosophers all. It’s an orientation, a disposition, a direction we’re all moving in. That, it seems to me, is the telos of the university. What are we even doing in the academy? Searching.

Another helpful follow-up piece. Thank you for writing this, Mike.

This passage stood out for me:

"If we want to be able to avoid these deficiencies and excesses, we need wisdom. We need to see the world as accurately and truthfully as we can so that we can discern what exactly professionalism, critical inquiry, and social justice means in any given situation. These virtues are not self-evident, and they are not calcuable. They are found in living the life of the mind in communion with our colleagues; in challenging ourselves through exercises in thought and practice; and in cultivating dispositions through interacting with fellow experts, commonly-held canons, and the animating situations of our vocation: the classroom, the seminar, the library, the laboratory, and, appropriately, the conference."