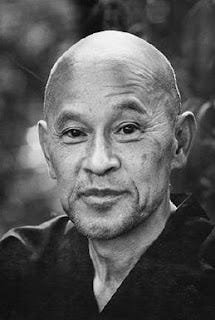

Book Review: "Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind," Shunryu Suzuki

As a practicing Stoic, I've sought out a variety of resources to improve my pursuit of virtue. One of them was this book, Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind, recommended by a friend who practices both Zen Buddhism and Stoicism. I recommend it for Stoics seeking to improve their meditation practice.

Overview

ZMBM is a series of lectures that Suzuki, a Zen Buddhist monk, gave to students in San Francisco, where he built a famous practice in the 1960s-1970s. The lectures are organized into three sections: "Right Practice," "Right Attitude," and "Right Understanding." Roughly, the "Right Practice" section, which I found the most useful, included advice, theory, and koans (short pedagogical Buddhist stories) about meditation practice, or "zazen." The "Right Attitude" section included a focus on emotion management, mostly consistent with mindfulness and Stoic approaches to emotions. The "Right Understanding" section focused on Buddhist metaphysics (which I do not subscribe to).

Useful Ideas for Stoicism

There were many useful ideas in this book for the Stoic prokopton. In particular, I found the concepts of big mind and beginner's mind to be consistent with Stoic practice and my own experience.

Big Mind

For the Stoic, "big mind" will likely resonate with logos or Nature. What is of practical import from Suzuki and the concept of big mind is the sense in which our purpose on this Earth is tied to a participation in the big mind--to be the big mind, the logos, living in accordance with Nature. Suzuki explains: "When we forget ourselves, we actually are the true activity of the big existence, or reality itself. When we realize this fact, there is no problem whatsoever in this world, and we can enjoy our life without feeling any difficulties. The purpose of our practice is to be aware of this fact" (p.66). This idea that we are part of this "big activity" (p. 65) might motivate us towards pro-social ends, as we can see our lives as part of a bigger picture. But at the same time, our "smallest particle of the big activity" (p. 65) humbles us, reminding us of how much this universe we must simply accept. The connections here to the Stoic virtues of justice and the view from above are very clear, and Suzuki's formulation of these ideas are useful for the practicing Stoic.

For Suzuki, "forgetting ourselves" is the key here, and it's part of the reason Suzuki says Buddhism is not expressible in language (p. 39) because it is an experiential practice essentially. To forget ourselves is to simply be in the world, being a part of the big activity, without worry or trouble. In Stoic terms, this sounds similar to fully accepting indifferents and desiring only what we can control. Suzuki's formulation of simply doing what we are doing, forgetting ourselves, being like a frog (p. 67; a story you must read to understand) has been a powerful heuristic for implementing some of the more abstract Stoic practices. What does it mean to desire only what you can control? It might mean simply being in the world, forgetting yourself. If I do that, then I certainly am not chasing indifferents or being perturbed by my aversions to things I cannot control.

Beginner's Mind

"Beginner's mind" is just like what it sounds like--the mind of a beginner. And as a teacher and student, I found this concept resonating with my own experience and with the educational psychology literature. Suzuki explains: "In the beginner's mind there are many possibilities; in the expert's mind there are few" (p. 2). The expert's mind has organized things which limits ideas; the expert's mind has accepted orthodoxies. The beginner can challenge fundamental assumptions of a field of practice in a way that an expert cannot. The beginner can see things that don't make sense that the expert has given up on or has accepted in resignation. Suzuki advocates for beginner's mind throughout the early part of the book, and it's a mindset I think is useful for teachers and students to try to adopt to make learning more meaningful.

For the Stoic, beginner's mind might closely align with the Discipline of Assent, for it's the constant vigilance against irrational thinking that the beginner's mind promotes. Suzuki explains: "In the beginner's mind there is no thought, 'I have attained something.' All self-centered thoughts limit our vast mind. When we have no thought of achievement, no thought of self, we are true beginners. Then we can really learn something" (p. 2). It's this honesty with ourselves and our intellectual humility--and the simultaneous rigorous pursuit of truth--that embodies a disposition so valuable to the Buddhist and the Stoic alike.

This practice of intellectual humility is one I've sadly failed at in key points in my life; Suzuki and my journey in Stoicism have helped me make progress in developing a compassionate mind--compassion for others and for myself. Suzuki further explains: "The beginner's mind is the mind of compassion. When our mind is compassionate, it is boundless. Dogen-zenji, the founder of our school, always emphasized how important it is to resume our boundless original mind. Then we are always true to ourselves, in sympathy with all beings, and can actually practice" (p. 2). For the Stoic, this ties the Discipline of Assent to the logos--when we practice this compassionate mind that rightly recognizes our own human fallibility, we are seeing the world clearly and living in the world in accordance with Nature.

Conclusion

With the concepts of big mind and beginner's mind, Suzuki can contribute a great deal to the Stoic's practice. The connections Suzuki makes between various ideas--such as between big mind and beginner's mind--invite curiosity and inspire new perspectives on established Stoic thought. The heuristics he offers throughout the book can help improve Stoic practice. And the disposition Suzuki instructs his students to cultivate invites the Stoic prokopton to consider how Zen Buddhism and Stoicism might be driving at helping us become the same--or different--kinds of people.

It is a book, as my friend and I learned, worth talking about over a good cup of tea as you both struggle with and discover what it means to live these ancient and challenging practices.